During the COVID-19 pandemic, misinformation about the novel coronavirus has spread almost as fast as the disease itself. But lest we think such conspiracy theories are a product of our social media-soaked times, a new student-curated exhibit in Lutnick Library’s Rebecca and Rick White Gallery shows that misinformation has always been virulent in times of crisis throughout history.

From the English Civil War to the French and Haitian Revolutions to Philadelphia’s Yellow Fever pandemic to the Vietnam War, crises make people reassess how they see the world. That is the story told in The Hundred Tongues of Rumor: Information, Misinformation, and Narratives in a Time of Crisis, an exhibit curated by history major Nick Lasinksy ‘23 that is up through July. Lasinsky used documents and artifacts from Haverford’s Quaker & Special Collections to create a story that spans centuries and borders, showing how information proves to be crucial in how people understand the world. “No matter where you are and where you live, you have to deal with the information around you,” said Lasinsky.

Lasinsky created this exhibit as the library’s Joseph E. O’Donnell Student Research Intern last summer. Over 11 weeks, Lasinsky learned archival work and improved his independent research skills through his work, which culminated in the exhibit. He chose to focus on times of crisis because of the malleability of people’s perceptions of truth and how fast minds can change. “Things move fast in a crisis,” he said. “Suddenly being able to persuade someone with facts, with rhetoric, is super powerful. One of the most interesting aspects of information is where it can be twisted and fractured and bent when people are under pressure.” Additionally, he was inspired by current crises–including COVID–and the ways the “dizzying” pace of information sharing today can make facts “twisted and distorted.”

When Lasinsky started his summer research internship in the library, working for Sarah Horowitz, head of Quaker & Special Collections, he was given the basic parameters of creating an exhibit focused on “information,” but it was his time in the archives that inspired him to focus on misinformation during four specific urgent historical moments.

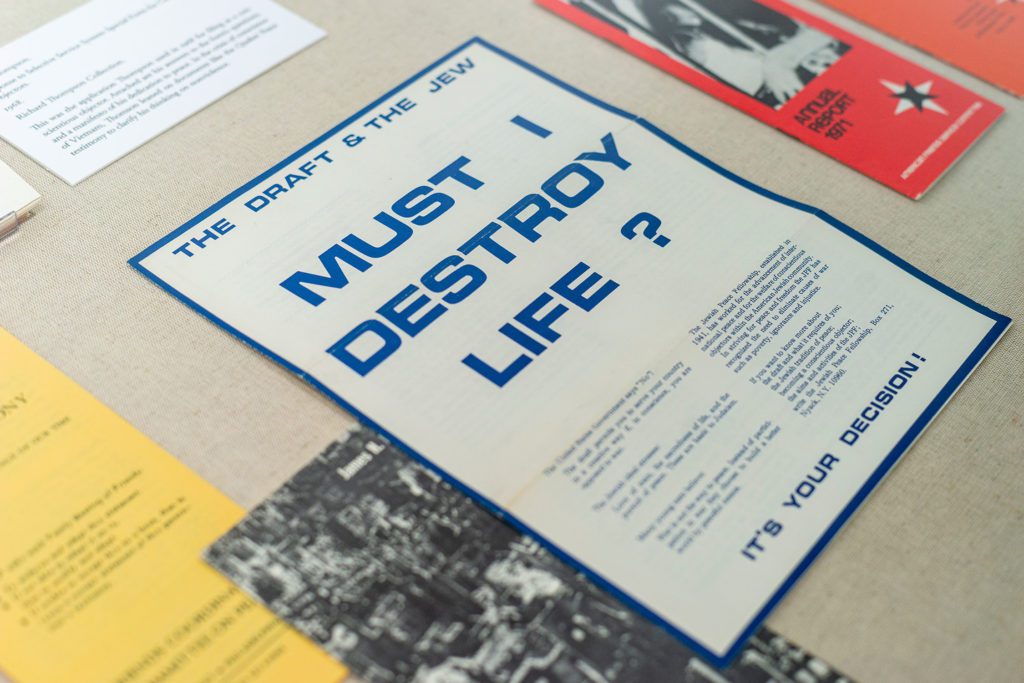

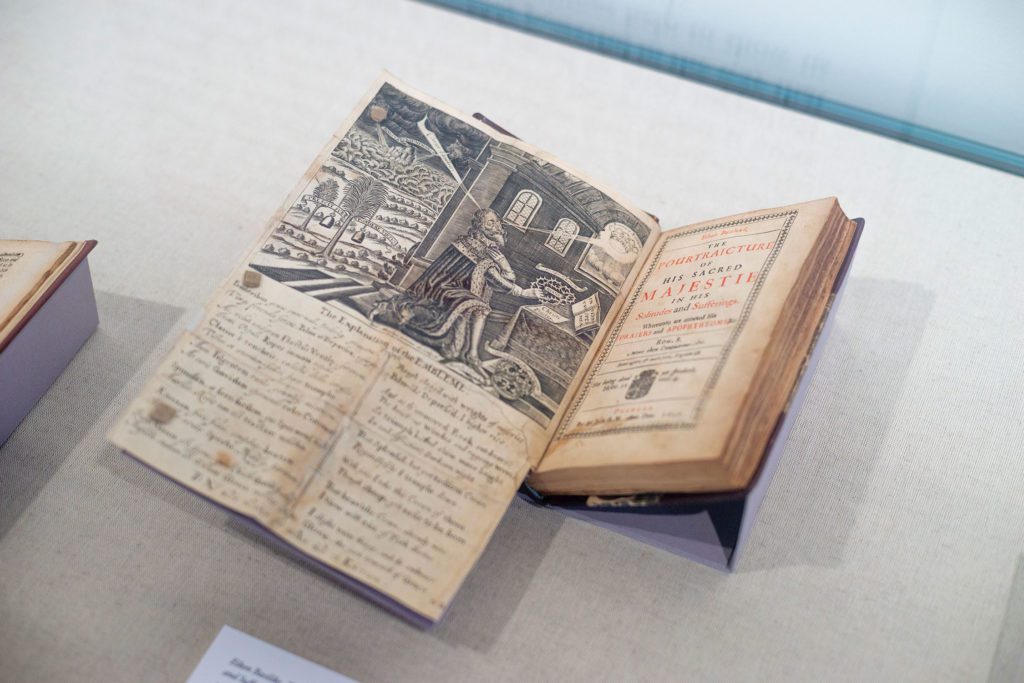

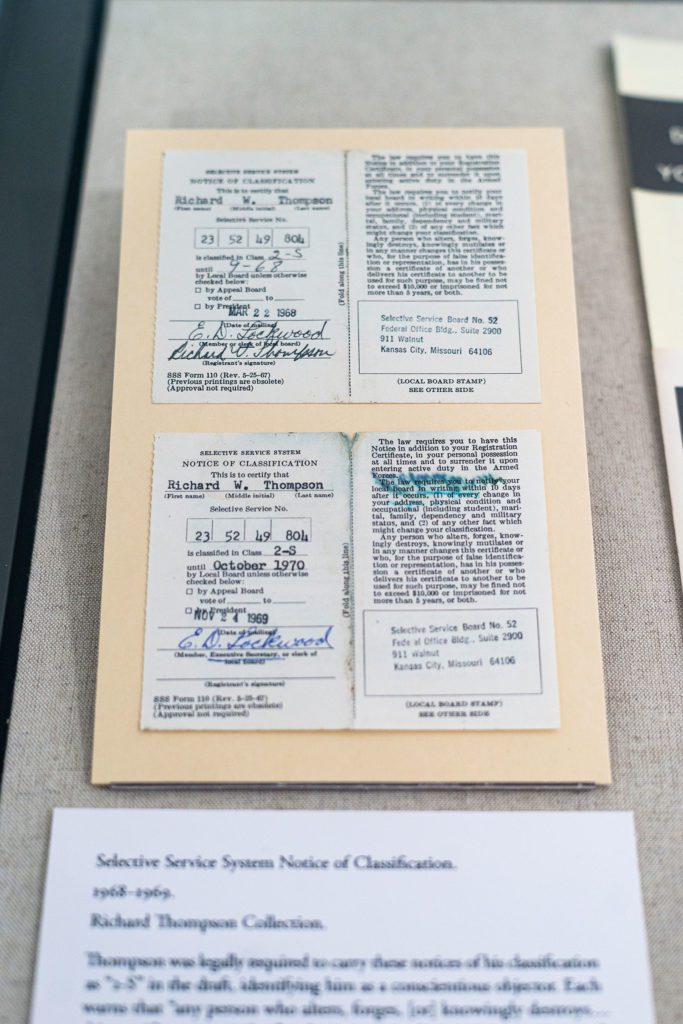

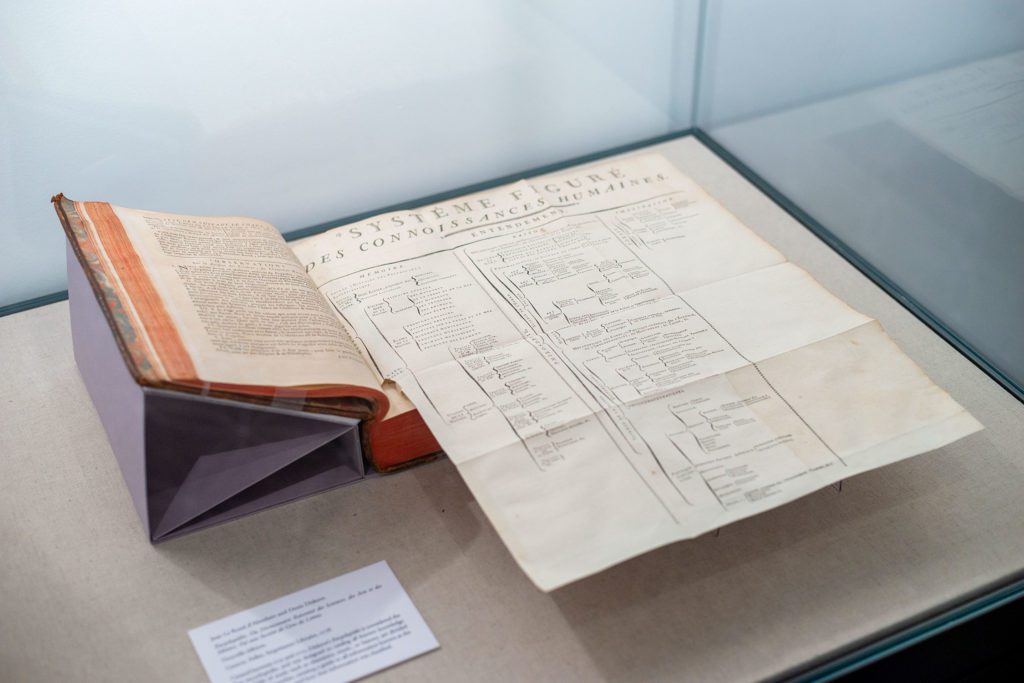

He was drawn to the 1640–1660 English Civil Wars, the late 18th-century French and Haitian Revolutions, Philadelphia’s 1793 yellow fever epidemic, and one man’s perspective on the Vietnam War from 1960 to 1973 because all of them were impacted by the use of propaganda and misinformation. Lasinsky uses pamphlets by William Prynne to portray the English Civil War as a crisis of religion, in which being accused of being a “papist” spurred fear from the community. Lasinsky emphasized the moral crisis over slavery among the revolutionaries of the French Revolution and how that debate influenced France’s response to the Hatian Revolution. He chose Philadelphia’s yellow fever endemic to portray how a natural disaster spurs a biological crisis using three volumes by Matthew Carey. His most contemporary feature, the Vietnam War, grapples with a crisis of consciousness, specifically by featuring Richard Thompson’s American Friends Service Committee pamphlets on pacifism. “I flirted with [featuring] the Chinese nationalist conflict, but [decided to feature] the French Revolution for the government and revolutionary aspect.”

A 1793 third edition of Matthew Carey's "A Short Account of the Malignant Fever Lately Prevalent in Philadelphia With A Statement on the Proceedings That Took Place on the Subject in Different Parts of the U.S.," which wrongly accused workers of the Free African Society of taking advantage of the poor. Photo by Patrick Montero.

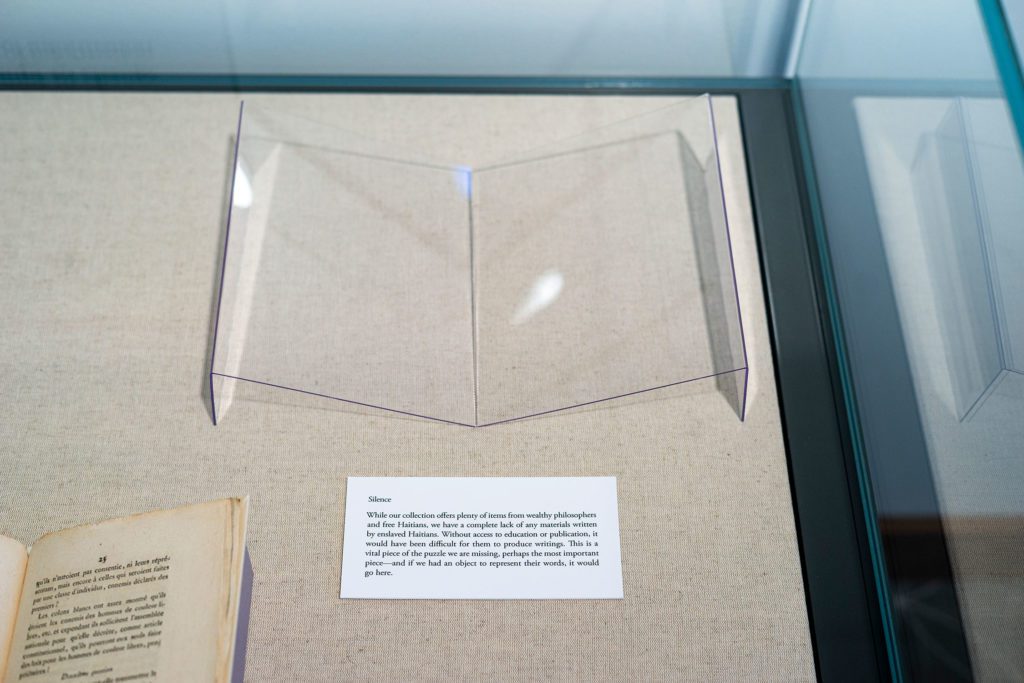

Once he decided on the events, he then found specific pieces from Quaker & Special Collections to best illustrate how propaganda impacts people’s writing and opinions. In this work, he realized the incompleteness of the stories and information he was reading, and, as a curator, he spotlighted that incompleteness by showcasing some empty book stands inside display cases with labels that explain the sort of perspectives or artifacts that he feels are missing from the exhibit or even from the larger historical record. “The historical record has gaps,” he said. “There are things that are deliberately erased from the historical record and things we just don’t have at Haverford. We don’t have the perspective of slaves during the French Revolution or women during the English Civil War. There’s sort of these gaps I want to acknowledge, so we have these blank holders to fill in a gap of information.”

“I think the way Nick chose to represent the voices that aren’t present in the exhibit, because such sources don’t exist or aren’t found in Haverford’s collections, is important and visually impactful,” said Horowitz.

Designing an exhibit required a different mentality than Laskinsky’s previous experience in academic research. Unlike an academic paper, he had to focus on the visuals and the audience, instead of just the ideas. “The endless challenge is distilling your ideas down into what is most important for people to get out of this, for your viewer to take from this,” he said.

Lasinsky hopes that people understand the importance of critical thought as well as empathy. All the pieces that he chose highlight the dangers of propaganda and how in times of crisis people have used fear to control others’ actions. In showing how gullible people can be, Lasinsky warns the audience to be wary of what they believe and to question why they believe what they believe. Though, this is not to say that he thinks people in the current age are superior to people of the past. Rather Lasinsky encourages the audience to empathize with the people both in and out of the exhibit.

“We’re not morally better than the people in the past,” he said. “We’re also prone to propaganda. I want to encourage a sense of empathy with the people of the past.”