Often, the best kind of learning can happen outside of the classroom. Students in history professors Lisa Jane Graham and Darin Hayton’s “Biopower” course last spring know this to be true. In class, they analyzed the concept of biopower, as coined by Michel Foucault, and reflected on the COVID-19 pandemic by studying the history of the intersection between scientific authority, technological developments, and public policy. To investigate further, the class worked with Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts and Head of Quaker and Special Collections Sarah Horowitz to scavenge Lutnick Library’s archives for materials that reflected historical practices of biopower.

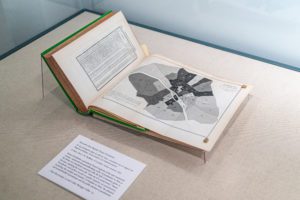

With an abundance of different resources, they worked together to curate Biopower: Reading Bodies, Regulating Practices for the greater Haverford community. The exhibition opened on Aug. 15 and will remain on view in Lutnick Library’s Rebecca and Rick White Gallery until December.

From the beginning, Graham and Hayton designed the course around an exhibition and coordinated with Horowitz on logistics and materials available. They believed exhibition curation would provide a unique learning experience for the students.

“Curating an exhibit encouraged students to revisit the object they had select a number of times over the course of the term as they developed richer and more nuanced analyses of that object,” they said. “Moreover, by grouping the exhibit around themes, students had to put their objects in conversation with other, related objects. That process was a key part of the experience we had imagined for the course.”

Biopower: Reading Bodies, Regulating Practices is split into five sections, each exploring an aspect of authority, technology, and public policy that contributes to the state’s “biopower” over citizens. The first section, “Madness and Confinement,” contains materials, such as a superintendent’s daybook, that document the perception of mental illness and highlight the power imposed on those diagnosed as “mad.” Interestingly, none of the materials represent the experience of a patient—all of them come from the perspective of an authoritative figure.

The section on phrenology, titled “Reading Faces: Phrenology and Physiognomy,” highlights the rise of pseudoscientific studies in the 19th and 20th centuries that drew connections between the structure of the human skull and mental and personality traits. These studies separated individuals’ biology into categories of “normal” and “abnormal”. The materials in the “Prostitution and Normative Masculinity” section challenge the norms of masculinity and highlight the experience of female sex workers, often historically victims of power and dominance by men’s sexual entitlement.

The “Water and the Creation of American Public Health” section contains materials that tell the story of the vital role of water plays in sanitation and hygiene in pre-20th-century society. Selected resources from the American Public Health Association detail the organization’s methods of maintaining power through regulation of water usage and eventual expansion to other nations.

The final section, “Epidemics: Facing Loss and Suffering,” highlights the feelings of despair and grief documented by those who experienced the worst of the yellow fever epidemic in 18th-century Philadelphia.

Graham and Hayton were more than pleased with how their students collaborated to select objects that fit the exhibition themes. “They drew on a wide variety of objects, showcasing not only their work but also the richness of our collections,” they said. “As with any new project, some moments were more challenging than others, but the students in the course and Jian Wei, who helped shaped the final version, did an excellent job overcoming those challenges. They did great work.”

Through engaging with these materials, students in the class had a better understanding of the ways in which the state can maintain control over individuals. This work also lent insight into the historical stakes of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the political practices of maintaining order through mask and vaccine mandates, enforced quarantine, and constant surveillance. “The most surprising thing I learned from this experience was how important and pervasive biopower is in our lives,” said Maggie McCarthy ‘25, a student curator in the “Biopower” class. “It’s something that we don’t think about much, but exists in almost every aspect of our world.”

Students from that class valued the opportunity to engage with the resources available in the library in creating the exhibit. “The ability to work closely with sources from Special Collections was my absolute favorite part of the class,” said McCarthy ‘25. “Getting to spend so much time working hands-on with primary sources helped me deeply engage with the material.”

“The opportunity to engage multiple times with not just the text of a primary source, but an actual book/pamphlet/scrapbook, etc. was always very interesting because there’s so much more to texts than what is actually written,” said Callia Weisiger-Vallas ‘24, another student in the class. “It is also just intriguing to me to be able to immerse myself more fully in the text as it exists alongside choices like font size, book size, paratextual information, images, sometimes advertisements in more popular texts, etc.”

Jian Wei ‘24, though not enrolled in the “Biopower” class, also contributed to the exhibition, writing the introductory parts of the catalog essay and helping physically install the exhibition. Wei enjoyed the experience of handling the materials. “Making cradles for the objects and designing the labels were such a distinct yet integral part of curating the exhibition that taught me a great deal about the hands-on aspect of the work,” he said. “My thanks to [Library Conservator] Bruce Bumbarger at the conservatory lab for his detailed and considerate instructions.”

The arrangement of the exhibition space was as much of a priority for the student curators as the content of the materials itself, said Weisiger-Vallas. “Definitely the most interesting and surprising thing I learned was how few people actually read the wall/catalog/display label text exhibition, and consequently potential strategies to engage an audience beyond a really great label. Everything in an exhibition becomes important, and understanding a little bit of the theory and motivations behind creating an effective exhibition was really useful and enlightening.”

On Sept. 30, Callia Weisiger-Vallas ’24, Michael O’Connell ’24, Kate Braverman ’25, and Maggie McCarthy ’25 discussed their curatorial work at an exhibition talk in Lutnick Library. They reflected on how their curation work molded their understanding of biopower, as well as the value they found in interacting with materials from the Special Collections.

“They offered complementary perspectives, each centered on the particular object they had analyzed for the exhibit,” said Graham and Hayton. “These four students represent the outstanding scholarship — thinking and writing — we can hope to see in our students.”